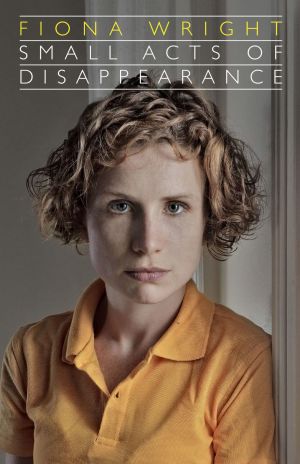

Small Acts of Disappearance

I couldn’t see myself as one of ‘those women’ – I thought that eating disorders only happen to women who are vain and selfish, shallow and somehow stupid; it took me years to realise that the very opposite is true, that these diseases affect people, men and women both, who think too much, and feel too keenly, who give too much of themselves to other people.”

…

Fiona Wright’s collection of “Essays on Hunger” are unique. Not because of the issue she tackles – although eating disorders, like all mental illness, are under discussed and heavily stigmatised – but because of how she writes about it.

Eating disorders affect nearly 1 million Australians, Anorexia Nervosa effects up to 1.5% of females and 0.5% of males. It has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder with risk of premature death up to 12 times higher than the general population. These deaths are not just caused my complications from the disorder, sadly many of them are suicides. Eating disorders are serious and sometimes fatal conditions and yet for some reason they are rarely treated as such.

My doctors never tire of telling me that we’re the unlucky ones. That in almost every other mental illness, treating the symptoms makes the patient feel better if only in increments…but for us, when we start to eat again…we feel worse, far worse, when we don’t have out hunger to protect us.

Our culture has a disturbing habit of both glamourising and stigmatising eating disorders – in life, film and literature.

Wright herself refers to this under the ironic name of sick-lit. Noting the unhealthy obsession we hold with both appearance and food obsession (Atkins, paleo, low-carb the list goes on). How many books or films (disturbingly this trend if often focused at teens) have you encountered that casually discuss, even promote disordered eating patterns, that in the same breath glamourise not eating as a solution to remaining thin and stigmatise over-eating or vomiting as “disgusting”.

Eating disorders rarely, if ever, develop without the sufferer first undertaking some form of diet. Whether this diet be for medical (as in Wright’s case), or aesthetic reasons it can act as a catalyst for deeper issues surrounding food. This other side of dieting, this obsession with personal appearance, but also with control, can, and does, have catastrophic consequences.

In a culture where we are constantly shown images of models (male and female) with bodies types that are unattainable without the work of skilled airbrushing, and who themselves are sometimes the product of disordered eating, is it surprising that we sometimes break in striving for an unachievable goal?

Life is rarely straight forward and mental health almost never is, so it is refreshing to read a text that does not purport to put forward a solution, a “fix”, but instead acknowledges the great complexity and confusion that is living with mental illness. In writing about her failure to understand why exactly “this” has happened to her, of what it means and of how to work towards recovery Wright is giving voice to many individuals’ experiences of mental illness.

There is no glamour in her words, no hidden pride or contempt. There is also no grand story arc – not fall into illness, period in therapy and then, ultimately recovery. Instead it takes unexpected turns, jumping from periods of illness to recovery, to treatment and back. Rather than being an ordered account it is a collection of thoughts, of progressions and regressions, of psychological musings and explorations of the portrayal of eating disorders in literature.

She began writing the book shortly after her first admission into day hospital, as she puts it: when the rug of my own delusion had been swiftly pulled out from under my feet. At one point in her essays Wright muses on the causes behind anorexia, prompted to start thinking by the seemingly simple question “Why do we want to be smaller?”

I think sometimes that the drive towards hunger, the drive towards smallness, is about precisely this: we feel so uncertain, so anxious about our rightful place in the world that we try to take up as little of it as possible. It is a drive to disappear that can only every succeed in making up more prominent, more visible because it makes us as different and offensive on the outside as we so often feel at heart.

The second half Small Acts of Disappearance is woven with discussions of literature, not just works that focus on eating disorders but broader books encompassing addiction and psychology. She examines texts as far apart as Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet – noting the way that Rose uses her hunger (for it is always referred to as hunger rather than anorexia by Wright) as a weapon to fight against a world she feels she is trapped in- to John Berryman’s Recovery an unfinished semi-autobiographical novel about addiction.

These discussions are central to the essays and are one of the aspects that make them so different from other writings about eating disorders. The essays themselves focus not just on Wright’s personal experience with anorexia – although there are many accounts of that – but on how we (the author, the reader and society as a whole) perceive eating disorders. The stigma we attach to them, the misunderstandings, the lack of resources and the changes in thought regarding treatment methods.

Small Acts of Disappearance is not a happy book. It will not make you feel better, and it is not an awe inspiring story of recovery. But it will make you think. Make you question presumptions and prejudices you may not know you hold. It will introduce you to new and old literature and it will allow you, if not an understanding then at least an insight into one of the most misunderstood and misrepresented mental health issues. It well deserves the numerous awards it has so far received and although not an easy read is the kind of book that stays with you long after you’ve turned the final page.

Written by Jean Roxon

If you are concerned that you or anyone you know may be struggling with an eating disorder you can contact the butterfly foundation on 1800 ED HOPE (1800 33 4673). Further information is available at The Butterfly Foundation and National Eating Disorders Collaboration.

Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our Mind Reader newsletter for monthly mental health news, information and updates.