Inmate Mental Health

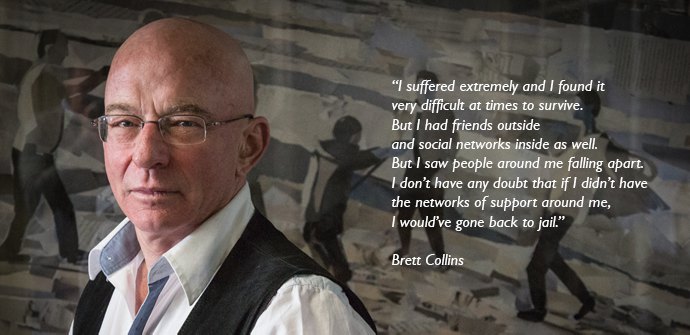

Harry Easton, in conversation with Brett Collins (pictured), explores the implications that the NSW prison system is having on mental health.

The health issues of prisoners within NSW jails are rarely placed in the national spotlight. There is a prevailing thought that those who have been convicted for a crime deserve to “do the time” behind bars.

Yet the isolated environment of jail can be a trigger point for mental illnesses to develop. There is also strong evidence of mental illness sufferers making up a large majority of the personnel in NSW correction services.

Brett Collins spent 10 years in jail during the 1970’s. He is now Co-ordinator of Justice Action, a community-based advocacy group that focuses on criminal justice and health systems, assisting those who suffer abuse form the system.

He says that a 2007 Australian Bureau of Statistics report on female prisoners found that 78% of men and 90% of women in the 12 months before sentencing had come to the attention of mental health authorities.

“Its a very significant statistic . Most people inside prison are likely to have a whole range of other social disabilities and mental illness as part of a spectrum of problems they have.”

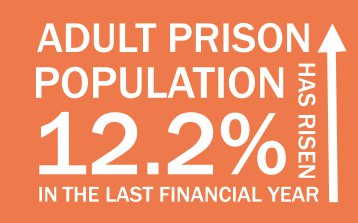

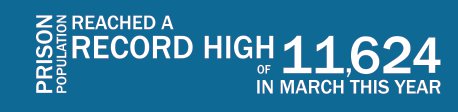

In January 2015 a report by the Inspector of Custodial Services, Dr John Paget, titled Full House: The growth of the inmate population in NSW highlighted a range of issues NSW jails are facing due to increasing imprisonment rates across the state.

Mr Collins highlights a specific line in the Inspector’s report that he believes emphasises the unsustainable environment that prisoners can experience.

“The foreword has a statement on the second page, where it states prisoners are held without a ‘modicum of dignity and humanity.’ Those words constitute the definition of torture.”

Mr Collins said there were a variety of factors that led to prisoners suffering from mental health problems.

“You’ve got isolation, loss of connection between people. It’s no surprise at all people end up with mental health issues. People are frightened when they are in jail; they feel as though they are likely to be preyed on. You end up with a tension for people trying to avoid interactions and avoid antagonising others.”

Deputy Director of the Sydney Institute of Criminology, Dr Garner Clancey, said the prison environment could compound underlying psychiatric issues that individuals may have.

“A prisoner suffering from a mood disorder might find that symptoms are exacerbated by entering prison, especially if it is their first time. Anxiety associated with entering the prison system, possible disruption to previous medication regimes, difficulties adjusting to routines… all have the potential to exacerbate any pre-existing psychiatric illness.”

The confined spaces of the prison cells can also heighten stress and anxiety. Prisoners are placed in these conditions for extended periods of time, as the Inspector’s report found that NSW jails had the lowest number of out-of-cell hours in the country.

Its findings show that for 16 hours a day, prisoners have no access to fresh air, programs, recreation activities, or contact with their families.1

Mr Collins says these restrictions are unacceptable.

Mr Collins says these restrictions are unacceptable.

“You have people who are normally working or moving around, who have social interactions with people, locked in an area that is the size of a bathroom. They are in there with someone else they don’t know. If you put two animals together in a cage you end up with tension between them. You throw 2 human beings who are under immense pressure and there are questions of dominance and respect… and these are the sort of tensions that make people fearful and concerned.”

Mr Collins also identifies disempowerment as a major psychological issue for prisoners.

“If you have depression outside of jail, then you can visit your family, you have a chance to talk to someone. In prison you can’t do that, you don’t have access to social support or peer mentors.”

The implications for prisoners are potentially fatal. Dr Clancey believes prisoners can become prone to self-harm and even suicide.

Earlier this year, an inquest was held into the suicide of an inmate at the Alexander Maconochie Centre in Canberra. The coroner heard that the inmate, who was on anti-psychotic medication, had to be moved out of the Centre’s mental health unit due to high demand for beds. The 30-year-old man died took his own life shortly after being transferred.

Dr Clancey says the NSW Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network (JH&FMHN) provides a range of health services to prisoners, but stressed that the demand was intensifying.

“The growing numbers of prisoners and the increasing prevalence of mental illness in the prisoner population

“The growing numbers of prisoners and the increasing prevalence of mental illness in the prisoner population

place ever growing demand on these services. More prisoners in cramped environments locked in cells for long periods will only result in greater psychological distress.”

The number of trained clinical staff has also become a cause for concern within the NSW prison system.

In a short statement, a JH&FMHN spokesperson said that a clinician examines every inmate as soon as practicable after being received into a correctional centre.

“Generally, the clinician is a suitably qualified, skilled, and experienced registered nurse. Inmates who are identified as having health conditions are referred on to specialist nurses and medical practitioners as required.”

However the Inspector’s report determined “that JH&FMHN has some difficulty in filling certain health positions, thus exacerbating waiting list times. There is a community-wide shortage of mental health nurses… on occasion a position is filled with an applicant who does not fulfil all the requirements.”2

Prisoners themselves are also wary of seeking clinician assistance and in some cases don’t want to be formally diagnosed as having mental illnesses. Mr Collins says prisoners do not trust doctors and are fearful of the system.

“As soon as they get diagnosed, they feel as though they are being targeted as conditions for people who are in mental health pods are worse than that of the major part of the jail. They lose social interactions with other prisoners. In the major part of the jail you have a chance to get a job, support, education but in the mental health pod you get none of those things.”

Even when prisoners apply for an appointment with nurses and doctors, there is a high rate of cancellations. The Inspector’s report found that 50% of appointments didn’t occur to lack of officers available to transport prisoners to the specialist.

Mr Collins also highlighted that prisoners themselves face losing key benefits if they visit the specialists.

“They don’t want to go to appointments, as they will lose their cell where they already have some stability, a place to themselves.”

The Inspector’s recommendations for change in the correction service system include increases in out-of-cells

hours, easier access to medication and prioritising staff roles. Mr Collins believes these are good starting points and highlights the possible use of electronic bracelets in the future.

“Instead of being sentenced, you can be monitored in an area for over an extended period. So you have the same control without the expenses and the destruction of locking people up. They use them now for people charged with sex offences, but they haven’t really been expanded into the general community.

“A lot of prisoners have come to us [Justice Action] and they think the monitoring system of the electronic bracelet has prevented them from doing illegal things.

“Then the money that is normally used to lock prisoners up can be spent on offering the positive services those inmates with mental health issues need.”

Dr Clancey believes that a community-based prevention strategy and a review of the isolating prison environment could decrease the number of prisoners with mental illnesses.

“Improving the availability of mental health services in the community will help to ensure mental illness is diagnosed earlier and more readily, rather than such diagnoses becoming evident for the first time in prison.

“Serious consideration needs to be given to the prison experience. Prisoners in NSW can spend very long periods of the day in their cells. Unstimulating and isolating experiences such as these will have negative impacts on prisoner well-being.”

Mr Collins agrees that early prevention is vital.

“If the health issues had been dealt with in the community, before the offence had occurred, then there would neither be an offence nor a victim. The economic cost would also be avoided…as well as the social cost, the cost to the victim. Clearly there is a need for proper community mental health care and social support.”

Written By

Harry Easton – Journalism Undergraduate UTS

References

1. Full House: The growth of the inmate population in NSW, State of New South Wales through Inspector of Custodial Services, Department of Justice, April 2015, p.11

2. Full House: The growth of the inmate population in NSW, State of New South Wales through Inspector of Custodial Services, Department of Justice, April 2015. p.50

Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our Mind Reader newsletter for monthly mental health news, information and updates.